Reverb

Projet Norma Jean

Olivier Dollinger

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

View of Olivier Dollinger’s exhibition Reverb - Projet Norma Jean, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2003 Reverb (le projet Norma Jean), 2003, Dispositif vidéo, DVD 15 mn © Olivier Dollinger 2003

« L’entretien » (par les voix françaises de Scully et Mulder, X-Files), Fondation Ricard, 2006 © Fondation Ricard

A conversation between Olivier Dollinger and Claire Le Restif.

Claire Le Restif: You are the only “performer” of your first videos: Apocalypse now (1996, 6 min), Currently on France Info (1996, 8 min).

Olivier Dollinger: I did indeed train as an actor. I didn’t go to art school. I created a theatre company. At the time I didn’t do shows but what I intuitively called “performances”. These micro-spectacles took place on the fringe of performances, before or after a show and never on stage, but around or outside the theatre.

C.L.R.: You very quickly had the intuition that what you were doing was not quite theatre. At the time you were only very little aware of the existence of this type of artistic language.

O.D.: It was indeed an intuition inasmuch as I’m self-taught. I had no knowledge of the presence of this type of artistic language in the history of art. These performances were a bit on the fringe of accepted conventions. Little by little they met an audience more interested in contemporary art. That’s how the transition for me was made from theatre to art. Some Carambar Jokes… (1996, 8 min): I fill this time with information in a minimalist performance. With carambars in my mouth I try to read the joke until I overdose. These performances are more interested in everyday cultural products than in big stories and are therefore close to the minimalist device of certain performances from the 1960s and 1970s. As a still possible space to say infra-thin and ordinary things.

C.L.R.: So your main concern seems to be with a body that is frustrated in its communication? For example A Green Mouse (1996, 1 min) and Some Carambar Jokes… (1996, 8 min) you just talked about?

O.D.: Through this series of videos, I tried to create a character close to the figure of the idiot. A character cornered by mass media over-information, losing his bearings with himself and his environment. A character unable to situate himself, unable to make sense of the external information that disturbs his daily life. The series is entitled Les vidéos-performances domestiques. In the video Une souris verte I almost entirely swallow a microphone at the back of my throat while singing the nursery rhyme Une souris verte, a way of using a tool linked to communication at its paroxysm, and by the same token of hindering and disrupting speech, the information becomes unreadable and gets lost, mixed with the hubbub of the body organs working and digesting.

C.L.R.: Your interest in the symptoms is already strong. Your photographs taken at the same period seem to be post-performance, consecutive to the action. Always central your body, your face. There are no external figures yet.

O.D.: At the beginning, the questions that preoccupied me could be summed up as “How can we still communicate when we are totally saturated with information? “What is actually communicated behind the incessant noise that surrounds us? ». It was during this same period that I made a series of self-portraits (1995, large format - passport photo framing) depicting the daily ills that alter the face through its holes, its gaps. All the communication orifices of my face, mouth, nose, eyes, ears, were disturbed by slight daily ailments.

C.L.R.: I would like to come back to your reference to the figure of the idiot. Is it as Clément Rosset understands it in Le Réel, a treatise on idiocy, or as Jean-Yves Jouannais envisages it in his book L’Idiotie? At the time of your first plays by the way, Jean-Yves Jouannais was putting on an exhibition called L’Infamie. The artists exhibited (Saverio Lucariello, Joachim Mogarra, Michel Blazy, Fabrice Hyber, Jean-Baptiste Bruant among others) took the risk at one point of leaving self-esteem aside, betting on sarcasm. This is an important moment for contemporary art. What was your position then, infamy or idiocy?

O.D.: Idiocy. It was then a possible posture to talk about my political position to the world and to art in particular. The real (as an artist) is what we have to struggle with. I am thinking for example of the representations imposed on us by our socio-cultural heritage which works within us and which we try to rework, to reorder to reformulate differently. The real is therefore in my work linked to a question of identity and its possibilities. I felt closer to idiocy than to infamy, a form of happy resistance, if I dare say so, a gentle irony, a state that allows us, perhaps through nonsense, to rediscover a part of innocence in the face of images. It’s true that in the mid-1990s, this became a recognised posture for many artists, officialized and integrated by the market and institutions. I then continued to work but in a direction where idiocy became less central to my work, less frontal and more deaf.

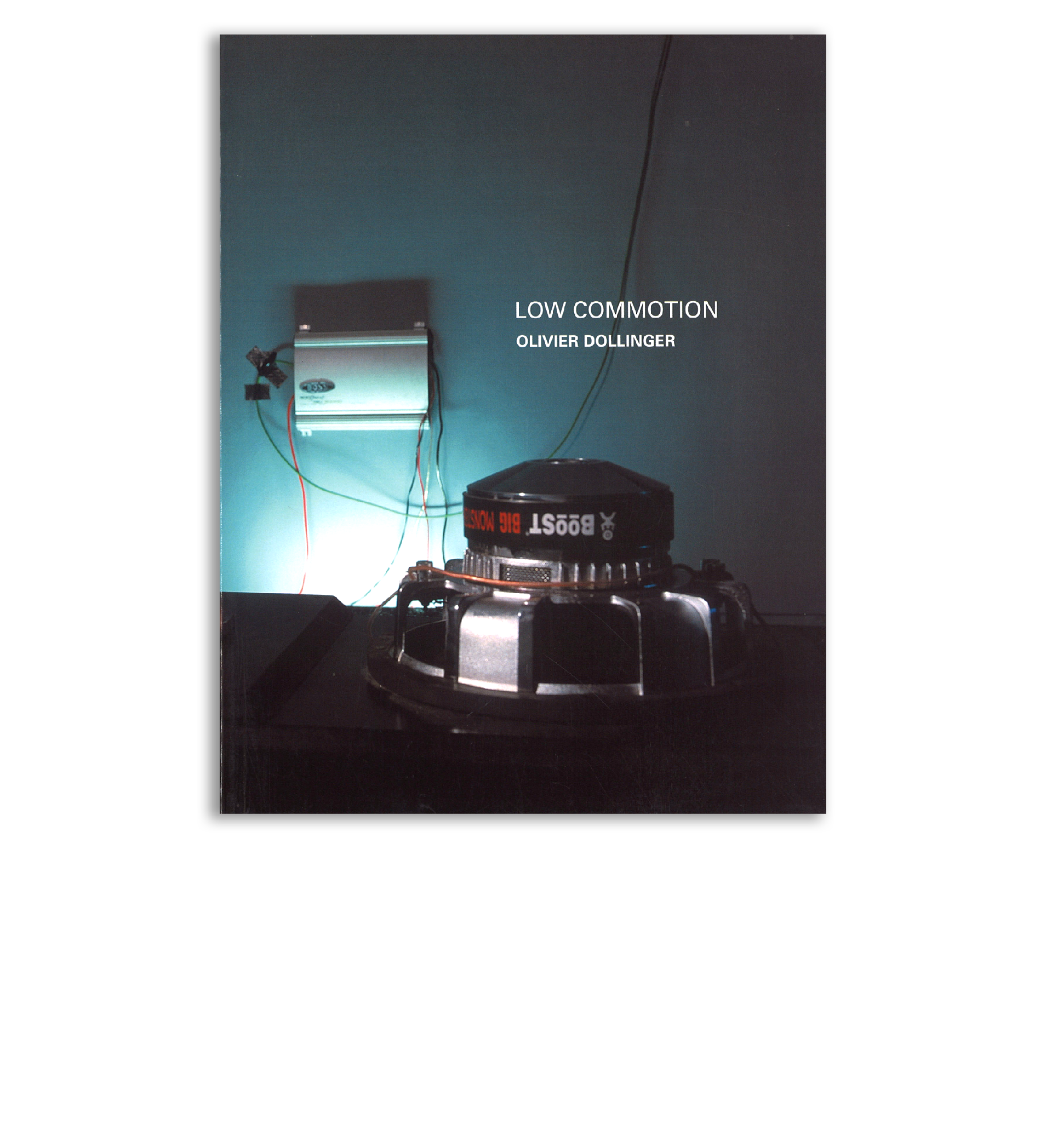

Nevertheless, there are reminiscences in my current work, it is also one of the possible angles of reading of a work like Over drive (2003, 6 min) which captures and stages the competitors in an SPL competition, a competition which consists of filling a car with powerful sound material and holding it in the passenger compartment for as long as possible for a few seconds under the effect of a decibel discharge.

C.L.R.: A central figure appears, who seems to replace you: “Andy” with the Rescucitate Andy kit. Another body on which you are going to act. This project lasted five years and it is fundamental. This work, on a form of reanimation, ends with the destruction of the mannequin!

O.D.: The first piece with Andy was produced in 1995 for a personal exhibition at Art 3 in Valence where I spent the week before the opening, alone in the space with the mannequin. It was a very big and empty space, I made him walk, I talked to him, I sang songs to him. The idea was to animate the exhibition space with the weight of what remains in art. How do you animate art? What do you do with art?

C.L.R.: The exhibition then consisted of projecting the images of the past week in the exhibition space. I am naturally thinking of Joseph Beuys’ work I love America and America loves me (1974).

O.D.: At the time I was represented by a gallery in Luxembourg and I had entrusted my model to the gallery owner for the duration of the exhibition. He put it in a corner and did absolutely nothing. He let it die. I had given him an instruction: “You do what you want with it! “I found that quite interesting in relation to the way the art market works. He told me after the exhibition “I watched him every day and I really didn’t know what to do with him!

C.L.R.: On the other hand, when you offer them “Andy”, the public is not lacking in imagination! Filmed behind closed doors in this “loft”, the scenes are in turn sadomasochistic, erotic, violent, and in any case disturbing each time. One person is benevolent! Léa Gauthier describes Andy in Le double jeu de l’image as “a relational lure, a perverse object on which desires or fantasies are projected”.

O.D.: Andy is a dummy used in the first aid pedagogical courses. What interested me about this object was its status. An unsurpassable contradiction, an object to which we try to give life again perpetually, an object on which we are forever striving in the void, something lost in advance, a nonsense that is somehow inscribed in the very function of the object. Andy seemed to me to be the ideal person to explore my concerns about notions of identity. A portable identity kit to explore and experiment with the relationship to the Other and the double. I used it as a fictional object to invest in. I proposed to my entourage to take “Andy” into their home to do what they wanted with it. One gesture = one photo. I made a slide show in loop and very fast, in different settings, atmospheres, emotions and feelings. The model came to life but kept changing identity, in perpetual search and reappropriable ad infinitum. Then I carried out a second project where I proposed Andy to students of a school as a fictional character to invest. The result was a film, each child invented a micro-script. As a final step, I placed Andy in an exhibition. Everyone could do whatever they wanted with Andy, in a closed room. They were warned that they were being filmed. What happened: the mannequin was totally destroyed. Most of the spectators unloaded violence on him repeatedly, incredible violence was unleashed. The mannequin no longer exists, it was completely destroyed, which ended the work in a natural way !

C.L.R.: Our first collaboration dates back to 2000, when I presented Collapse in an exhibition devoted to performance art. Collapse is an in-camera video where you hide under a big Pokémon head. You choose Pikachu, the children’s favourite. Big head, small body, not quite a puppet but not far away. For me this video is a hinge. It’s almost a still time, almost a photo. Communication and non-communication, autism again, how do we live in this closed-door world, a world full of threads that go nowhere? Communication plus the puppet plus the figure and plus the performance.

O.D.: And the image as well. Pokémon is a popular image that arises at a specific moment in time all over the world. For me there are virus-images, just like computer viruses. They invade the media space and infiltrate our minds and therefore also our bodies for a while.

Collapse is an apnoea video in which I experience the Pokémon state through the most famous cartoon character, Pikachu. I experience a physical state, a state after the performance and from within the communication. The oversized head of the Pokémon is a metaphor for the global market culture that is invading my living space.

C.L.R.: The Tears Builders (1998, 30 min): an amplified, inflated, unnatural body, a bit like Pokémon, wanders through space. Burning (1999, 3 min): you invite a young guy to enter a symbolic place, the “art centre” with his scooter. He crashes into the corners of the place, brakes and leaves tyre tracks. Over Drive (2003, 6 min): characters lock themselves in cars. The three works, three closed-door sessions, deal in some way with the construction of male identity through stereotypes.

O.D.: Three closed doors through which the “masculine” seeks above all to build himself up in a lost desire for power taken to extremes. In The Tears Builders it is played out through the mastery of the body, in Burning through the mastery of mechanics, and in Over Drive through the mastery of technology. In each of his pieces, the aim is to include the spectator in the psychological state of the protagonists. In Over Drive, it is the gallery space that is literally superimposed on the psychological space of the competitors.

C.L.R.: In The Tears Builders, it is no longer you who are on stage.

O.D.: In the videos you refer to, the performance has somehow become more complex and shifted from my body to others’. It is a question of the people invited to participate in my protocols to replay their reality in another reality. The body of the bodybuilder, disarticulated from its environment and its usual function, enters in struggle with its own representation. There is a shift that takes place between representation and presentation as much for the character as in my way of filming the action, which always tries to be very close to the bodybuilder’s breath. This in-between, this destabilising indeterminacy for the bodybuilder allows me to make him pass from an icon of omnipotence to an icon of emptiness. A floating appears in this suspension of intentions, spatial as well as temporal landmarks, since the bodybuilder’s only instruction on my part was to put himself in the psychological and physical state of mind of the moment before going up on an exhibition podium. The camera in this room is active in the sense that it captures as much as it triggers complex emotions in the bodybuilder that destabilise him and turn over the spectacular image in which he is caught.

In these pieces, the challenge is to merge performance and the modalities of reality TV in The Tears Builders, performance and the aesthetics of documentary film in Over Drive, performance and a certain grammar of cinema in Le projet Norma Jean.

C.L.R.: In your work you generally choose physique, facial types, at the passage between adolescence and adulthood.

O.D.: Andy, the model was also between two ages and two sexes depending on the lighting he could be as much female as male. Adolescence is one between two worlds where everything is possible, where everything can be played out, where nothing is defined, it’s a state of instability in which the child you were comes into conflict with the adult you will be. So it’s a time and a space of resistance and intranquillity and that’s why I’m interested in this moment, like a time when things can be replayed ad infinitum.

C.L.R.: In Reverb (the Norma Jean project), produced for Crédac in September 2003, the female figure appears. The work on the image, behind closed doors, the stretching of time, identification, mimicry, come back. Nevertheless, it is a new approach?

O.D.: It’s the same intuition: to open up an image, an image that we all carry within us, to reinvest it and inhabit it differently. Contrary to The Tears Builders where the duration (30 min) allowed me to see the character in different states and thus crack the spectacular image, in The Norma Jean Project hypnosis is the new element that allows me to reinvest a frozen image differently, a bit like an archaeologist who would go searching the unconscious in search of the original image that pushed these women to become actresses.

C.L.R.: What is the genesis of The Norma Jean Project?

O.D.: My first idea was to call upon two actresses who belong to the European film culture: Jeanne Moreau and Anouck Aimée. I wanted to make them relive under hypnosis certain scenes, certain bits of dialogue through the great roles they had played during their careers. The question for me was how this collective memory is combined with individual memory. But in the end, I was more interested in the status of the image, so I went looking for the icon: Marylin Monroe. From then on, Los Angeles appeared to me as the central city of the film industry. One inhabitant in three works for this industry. That is why I chose Los Angeles as the destination for this work.

C.L.R.: What was the scenario?

O.D.: Hypnosis allows me to open the image, to stretch it. The hypnotist’s voice accesses the actresses’ unconscious and slowly makes two spaces, generally separated from the psyche, juxtapose. For a short moment the conscious and unconscious of the actresses, the real and the virtual, open a new space and this psychic space seems to me characteristic of our time, where past and future, near and far, intermingle, losing their resolutions, their respective territories.

I chose this room for its specificity. The bed at the back is on a platform, as on a small stage, that is to say that what is most intimate, the bed, is already on stage. There are three spaces in the video which now form one, the bed (backstage), the small lounge (the stage) and the city of Los Angeles (the hall). These three spaces, which are usually independent and enclosed, are now one and through this arrangement I try to point out a new relationship to the intimacy resulting from its commercial spectacularisation. Los Angeles is the biggest image factory, it is there that our most intimate representations are made, the representations that govern the world come out of the image factory that is L.A., and it seemed right to me to replay these representations within the factory itself and those through the factory workers.

So this project also questions the city of L.A. in its relationship with the entertainment industry. The Hypnotist I chose is also a scenographer and works in Hollywood, he directed scenographies for Madonna and Marilyn Manson’s clips, in a way for me it was as if the show hypnotized the show…

C.L.R.: You didn’t do a casting ?

O.D.: Not in the classic sense of the term. It’s not the quality of the play that interested me, but the way they carried Marilyn inside them, the way they live daily with this iconic character. So it was more a discussion than a casting that decided on my choice. One of them is a fan of Marilyn Monroe and collects unpublished photos, another has played the role of Marilyn Monroe several times and this character has stuck to her ever since, yet another is campaigning to rehabilitate a healthy image of the star on Hollywood Boulevard. In short, each had, in a way, strong links with Marilyn Monroe.

C.L.R.: Finally, you are behind the camera. Is it you or the hypnotist who conducts the operations? Who is directing?

O.D.: I’m more interested in capturing than in directing. In a way, I try to leave the staging open to the accidents that can be caused by the architecture of the space, to the events of light and sound. Just like in The Tears Builders, where the character was staged in front of the camera and was in charge of his own image. The staging was therefore shared by the different protagonists of the protocol. It is in a way “Open Source”; everyone can appropriate a part of it.

C.L.R.: Gathered in the same space, their bodies sometimes look for each other. Nevertheless each one seems to be in great solitude. Each one is turned towards herself and not towards the others. They give themselves over to be seen, but this remains very intimate.

O.D.: The soundtrack of the video mixes the direct sound of Los Angeles coming from the traffic on Hollywood boulevard and the voice of the hypnotist in the hotel room who slowly interferes in the psychic intimacy of the young women. The soundtrack thus juxtaposes urban space and intimate space, creating an indistinction between these two territories. The indistinction also stems from the fact that we never know if they are playing or if they are “played” by the hypnotic injunction. The Norma Jean project can also be read as a contribution to the situation of political power in the United States and more particularly in Los Angeles, where Arnold Schwarzenegger has just been elected governor. Since Ronald Reagan, the United States has been moving towards a performative conception of the world. Arnold Schwarzenegger is the final stage in this evolution where the boundaries between an actor governor, therefore fictitious, and an authentic governor, therefore real, have been completely erased. The Norma Jean project thus points to a whole game of erosion of the boundaries between the intimate and the collective.

C.L.R.: The Norma Jean project is shown in a room that has all the characteristics of a movie theatre, without the seats!

O.D.: The Crédac space was originally intended to be a movie theatre and it has kept some of its architectural features, a bit like a movie theatre skeleton. I thought of the installation as an echo of this original function, a way for me to be equally attentive to the context and to take into account the place where my work is set.

Artist biography

-

Olivier Dollinger was born in 1967. He lives and works in Paris, France.