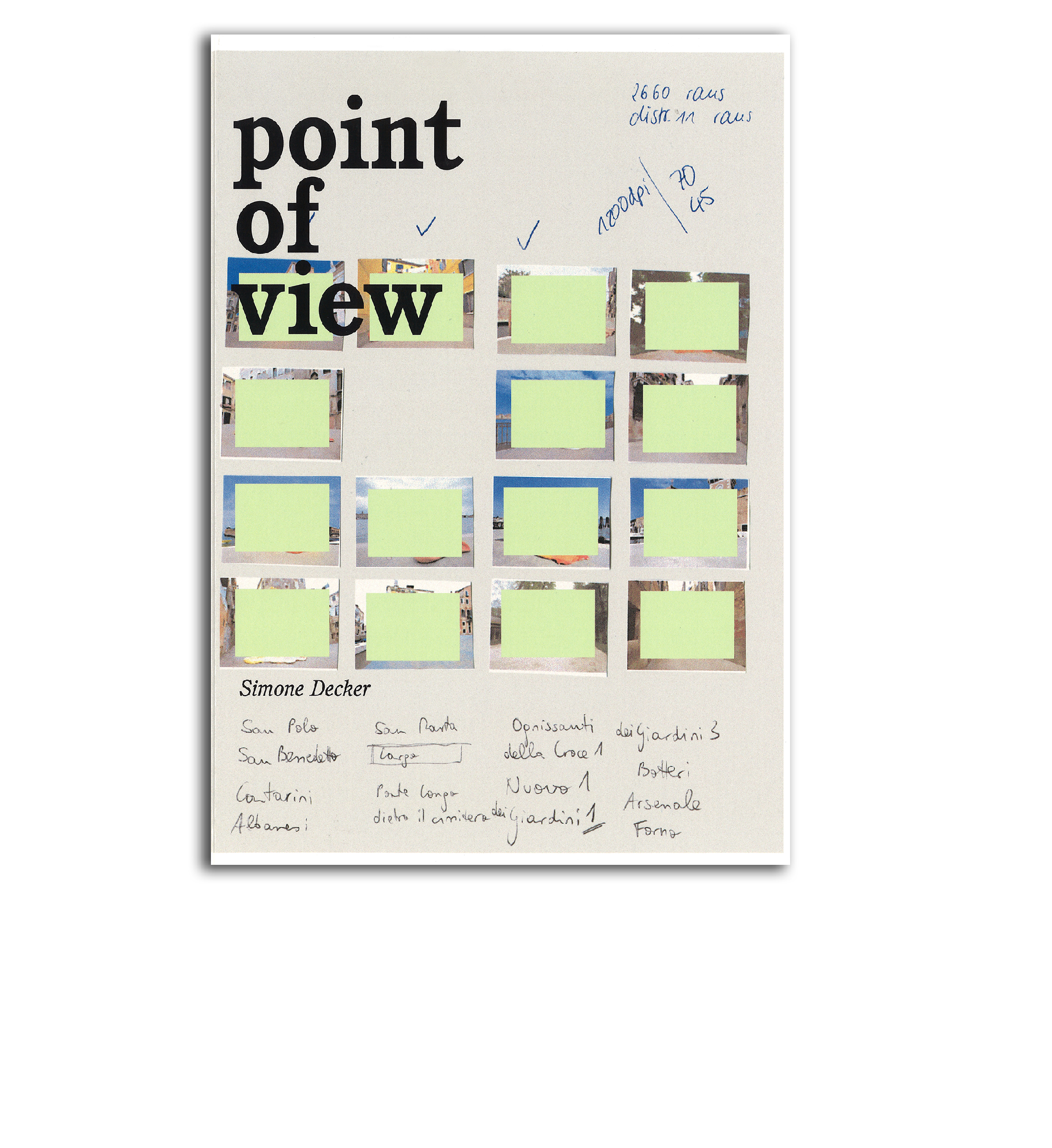

Point de vue

Simone Decker

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 Lenka, Blaise, …, 2004 (the work’s title changes according to the regional patronymic calendar wherever it is exhibited) Recently in Arnhem, 2001. Sonsbeek 9 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 Lenka, Blaise, …, 2004 (the work’s title changes according to the regional patronymic calendar wherever it is exhibited) Recently in Arnhem, 2001. Sonsbeek 9 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 A couple of full moons, 2003/2004 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 A couple of full moons, 2003/2004 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 Ghosts, 2004 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 Ghosts, 2004 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

View of Simone Decker’s exhibition Point de vue, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2005 Ghosts, 2004 © Photo : André Morin / Le Crédac

Raising Ghosts (extract)

Another work by the artist, in an entirely different style, confronts its viewer with an equally surprising optical phenomenon. A couple of full moons (2003/2004) is a showing of a film shot on a night when the moon was full. As it turns out, there are two moons that appear on the screen. There is nothing very mysterious about this, as the camera has recorded both the moon and its reflection on the lens. As the lens is curved, depending on the angle of the shot, the two moons are not necessarily perfectly superimposed. Furthermore, to show this film, Simone Decker has designed a peculiar viewing contraption: a kind of large telescope several metres long at the end of which is the projection screen. Unlike the theatre set which adds depth to the stage scene by taking on a gradually shrinking funnel shape, this device gets bigger, so as to resemble altogether a tunnel and leave an odd question mark over the distance from the eye to the screen. You might almost think you were dealing with one of those scopic devices so common in the early days of show business. Be that as it may, with this faintly absurd effect, the experience of viewing the film with the two moons is dramatized and placed almost on a scientific footing. The film camera has produced a second moon in the same way as the still camera takes tiny sculptures and turns them into monumental ones… »

“ …In 2004, Simone Decker returned to this practice of the imprint she had previously experimented with for Untermieter, in an astonishing set of pieces entitled Ghosts (2004). For these the artist took imprints of a number of sculptures taken from a broad range of periods, styles and qualities, and all located in the public spaces of Luxembourg. She then used these to make casts with a photoluminescent coating which, when bathed in daylight, stores it up and emits that light once darkness has fallen. Some of the resulting sculptures have been lined up on the roof of the “Aquarium”, the architectural appendix on the front of the main Casino building, where they stand out at night in the eerie, ghostly yellow light. Others, perhaps even more strikingly, have been placed in the obscure cellars of the building where they play their role of ghosts to perfection, when the phosphorus starts to give off its glowing effect, once the eye has taken the couple of minutes it needs to adjust. A ghost is the double of someone who is dead. Are we to take this to mean that Simone Decker’s phosphorescent casts are replicas of sculptures which, whatever their respective merits, have died of exposure, if not overexposure, in public spaces? Despite the formal novelty they inject into the artist’s output, the Ghosts tie in with certain concerns seen in earlier pieces. Consisting in the distance, both physical and chromatic, set up between a cast and its model, the idea here is close to that of a work like Untermieter. Even more surely than with Untermieter, Simone Decker’s ghosts of sculptures are to be viewed while bearing the photographs in mind. The insignificant architectures of the So weiß, weißer geht’s nicht series become like ghostly apparitions of themselves under the camera lens and the beams of powerful spotlights. Like the Ghosts, they draw their chimerical new lease of life from the night. As for the photographs of Chewing in Venice, 20 pavillons pour Saint-Nazaire, Pavillons im Musterbau und drumherum or Glaçons, their aim is not so very different from that of Ghosts as might at first appear. The photographic images seek to establish the monumental reality of ghostlike sculptures; the phosphorescent casts turn sculptures that have actually survived long enough to outlast any significance they may once have had into ghosts, to restore them to reality. Producing in this way a replica of a city feature that people seem to have lost sight of is also the subject of a work like Water Tower (1998) by Rachel Whiteread, a translucent resin cast of the volume of water contained in one of those rooftop tanks that are a feature of the New York skyline.1 Its presence, at once familiar and enigmatic, makes Water Tower another kind of ghost. Like Ghosts, such a project possibly indicates that in our postmodern, post-utopian age, ghosts are really all we can see any more…

(1)See Louise Neri, Looking Up. Rachel Whiteread’s Water Tower, Public Art Fund, New York City/ Scalo, Zurich - Berlin - New York, 1999.

Michel Gauthier

In Catalog Point of View

Co-edition Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry - le Crédac / Le Casino, Luxembourg, 2005

Translated from French by John Lee

Video(s)

Film of the exhibition © Claire Le Restif / le Crédac

Artist biography

-

Born in 1968 in Esch-sur-Alzette, Luxembourg. Lives and works in Frankfurt, Germany.