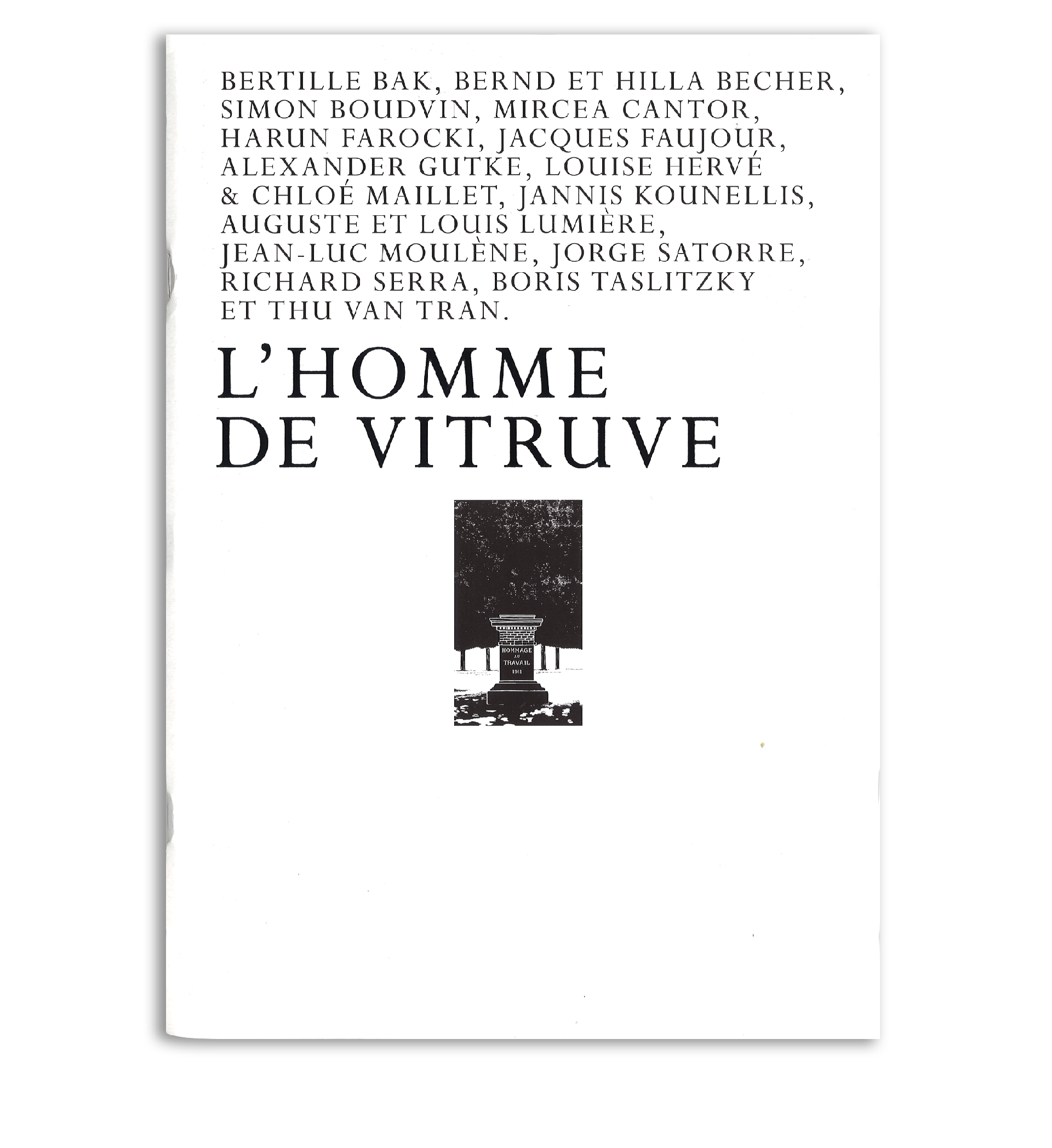

L’Homme de Vitruve

Group show

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Auguste et Louis Lumière, Sortie d’usine, 26 mai 1895, Collection Association Frères Lumière. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Jorge Satorre, La Part maudite illustrée, 2010, 90 paintings on wood (20 × 24.8 cm), wooden box (25 × 158 × 28 cm), 33 offset plates, Production: Le Grand Café, Saint-Nazaire © Photo: Marc Domage / Le Grand-Café, Saint-Nazaire, 2010.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Jannis Kounellis, Sans titre, 2003, twelve steel bases, black fabric, charcoal, approx. 120 × 40 × 40 cm (each). © Photo : André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Jean-Luc Moulène, Objets de grève, 1999-2000, Cibachrome photographs under Diasec on Yellow Forex, 49 × 38 cm, brochure available to the public. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac. Courtesy Galerie Chantal Crousel et Jean-Luc Moulène / ADAGP, Paris 2012

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Jean-Luc Moulène, Objets de grève, 1999-2000, Cibachrome photographs under Diasec on Yellow Forex, 49 × 38 cm, brochure available to the public. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac. Courtesy Galerie Chantal Crousel et Jean-Luc Moulène / ADAGP, Paris 2012

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Mircea Cantor, Double Heads Matches, 2002, Installation : video (color, sound, 17 min 20 s), matchbox, poster. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Harun Farocki, Vergleich über ein Drittes (Comparison via a Third), 2007, 16 mm film transferred to digital Betacam in double projection, 24’, color, sound. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Harun Farocki, Vergleich über ein Drittes (Comparison via a Third), 2007, 16 mm film transferred to digital Betacam in double projection, 24’, color, sound. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Thu Van Tran, D’Emboutir à Lire, 2010-1012, Showcase, books chosen by the workers of the former Renault factories in Boulogne, automobile stamping parts, Production: le Crédac, 2012. Écrire, 2009, Printed paper, methylene blue. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Bertille Bak, Cité n°5, 2007, Black ballpoint pen on paper, 21 × 15 cm, Collection FRAC Aquitaine. © Jean-Christophe Garcia.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. From left to right: Bertille Bak, Court n°3, 2007 Boris Taslitzky, Le Jeudi des enfants d’Ivry, 1937 Jacques Faujour, Bords de Marne à Bonneuil, 1984, Bords de Marne à Saint-Maur, 1986, Ville de Créteil, 1989, Douves du Fort d’Ivry, 1989 © Photo : André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Louise Hervé et Clovis Maillet, L’un de nous doit disparaître, 2012, Installation : Bookends, paperweights and lectern that once belonged to Maurice Thorez (Thorez-Vermeersch collection, Archives of Ivry-sur-Seine), booklet including an unpublished short story. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac.

Exhibition view, L’Homme de Vitruve, Centre d’art contemporain d’Ivry – le Crédac, 2012. Simon Boudvin, FAÇADE 01 (Liège), 2010, Two color photographs (77 × 61 cm), plaster model, co-production of the artist and the churches, contemporary art center of the city of Chelles. © Photo: André Morin / le Crédac. Courtesy galerie Jean Brolly.

Artists: Bertille Bak, Bernd & Hilla Becher, Simon Boudvin, Mircea Cantor, Harun Farocki, Jacques Faujour, Alexander Gutke, Louise Hervé et Clovis Maillet, Jannis Kounellis, Auguste et Louis Lumière, Jean-Luc Moulène, Jorge Satorre, Richard Serra, Boris Taslitzky, Thu Van Tran.

Curatorship: Claire Le Restif, assisted by Léna Patier

Planned with the Crédac’s new venue in mind (the Manufacture des Œillets, or Grommet Factory, in Ivry), this show features works of art that touch on the industrial world, the gradual disappearance of shop-floor know-how, and union movements in factories yesterday and today.

The exhibition took shape around a realization, that the famous Manpower logo with Leonardo’s Vitruvian Man, the symbol of man at the center of work, had in fact disappeared a few years ago in favor of an abstract image. L’Homme de Vitruve brings together international artists who are acutely aware of the phenomenon of deindustrialization and the past of now abandoned factories, and who view the work world as an apt subject for an archeology of the present age.

The Grommet Factory is emblematic of the history of Ivry, which only yesterday was still an industrial town. The building, which also houses a school of architecture and graphic arts, and soon a national center for theater, is also representative of another phenomenon, the current vogue in refurbishing and repurposing factories as art venues that transform this heritage into a cultural and tourist destination.

Not far from where visitors can watch Workers Leaving the Lumière Factory (1895), a film by the inventors and pioneering filmmakers Auguste and Louis Lumière, a selection of albums from the 1980s British music scene is on display. The musical trend of those years, fittingly symbolized by the Factory Records label, represents this reappropriation of postindustrial sites by artists, initially as production areas and later as venues for getting art and music to the public.

The painting by Boris Taslitzky called Le Jeudi des enfants d’Ivry (Thursdays, for the Children of Ivry, 1937), where we can make out the Manufacture des Œillets in the background, illustrates in fact the first recreation centers at a time when intellectuals and artists were also taking part in workers’ struggle for better conditions. And with his photo series Trente-neuf objets de grève (Thirty-nine Strike Objects, 1999-2000), Jean-Luc Moulène places himself in this same tradition, refreshing the collective memory through these objects, tokens of famous union struggles. Nine photographs are presented along with a brochure containing the whole of the series and offered free to visitors.

Louise Hervé and Clovis Maillet are highlighting a selection of objects that once belonged to Maurice Thorez (director of the French Communist Party from 1930 to 1964, and a member of the French National Assembly representing Ivry) and are conserved in the Municipal Archives of Ivry. The man who titled his autobiography Fils du Peuple (Son of the People), and hailed books as tools for emancipation, is also the starting point of a science-fiction story and a performance, both produced by Crédac for the show.

Now a production site of a different sort, artistically directed in this case, the Manufacture has been taken over by artists, who, like archeologists, ethnologists, archivists, or engineers, weigh the legacy of workers and commemorate this heritage through their own creative endeavors. Opposed to productivity, their pieces highlight the process of work and its human context.

Thus Jorge Satorre, in suspending his project La Part maudite illustrée (2010), an illustrated version of Georges Bataille’s essay The Accursed Part, put into practice its central idea, i.e., the part of loss and wastage that exists in any sort of production. Likewise, in Le Nombre Pur selon Duras (Pure Number According to Duras, 2010-2012), Thu Van Tran sought among other things to draw up a complete list of all the workers who had once been employed in the Renault factories in Boulogne-Billancourt, an idea first suggested by Marguerite Duras.

Simon Boudvin offers an update of the history of a Maison populaire, a kind of early popular recreation center, in Liège. The center, a refuge for workers in the union struggles in Belgium, was housed in a mansion dating from the 17th century (FAÇADE 01 (Liège), 2010). Through a model of the building’s façade and photographs of some of the original stones that have been conserved, the artist points up the different intentions that are at work in the act of conserving and, in the process, how history is constructed.

Bertille Bak records the façades of corons, those traditional row houses in proletarian towns of Northern France, and recreates an assembly line for French fries manned by children from the housing projects (Cité n°5, 2007). Meanwhile, Mircea Cantor collaborated with the workers of a match factory in Romania to produce a series of two-headed matches from discarded ones at the foot of their machines (Double heads matches, 2002). His film celebrates manual skill, just like the 2007 film by Harun Farocki called Vergleich über ein Drittes (Comparison via a Third), which documents the different ways bricks are made around the world.

Jacques Faujour, on the other hand, documented deindustrialization by photographing productive leisure activities along the banks of the Marne in the 1980s, showing angling and gardening against a backdrop of industrial wastelands. These photos act like humanist echoes of the implacable typologies of Bernd and Hilla Becher (Pit Heads, 1970-1988 and Blast Furnaces, 1970-1989).

The sculptures of Jannis Kounellis (Untitled, 2003) and the film by Richard Serra (Hand Catching Lead, 1968) remind us, with their strong emphasis on materiality, how seriality and industrial materials (steel, coal) have pushed the human body to rival machines by inventing new kinds of behavior. The Moebius strip devised by Alexander Gutke (Measure, 2011) introduces notions of continuity, loops and movement.

There is an empty pedestal still standing in Ivry that once held a sculpture in the 1950s. Sporting the inscription “Homage to work,” this non-monument strangely resonates as a local and universal symbol of the “Vitruvian man,” who has been rendered invisible.

Drawing on the history of the industrial past and present, these artists sketch out a recollection that differs from what one finds in the work of the historian or sociologist, an active, productive recollection that tries to place once again the human body and the social at the heart of societal issues today.

Video(s)

Film of the exhibition by Bruno Bellec © Le Crédac

Events & meetings

Partnerships

Media partners : Journal des Arts and artnet.fr